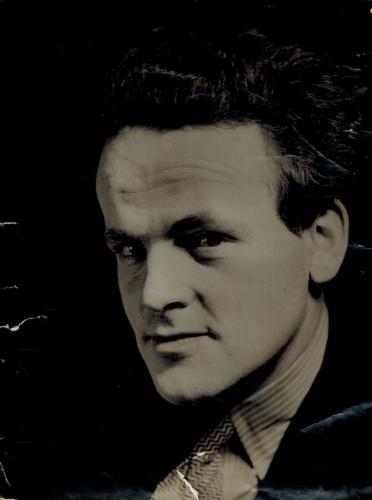

Bertus van Lier

Composer Bertus van Lier was a versatile and determined intellectual. From the start of World World II he upheld his principles against the occupier. During and after the war he maintained this attitude towards those colleagues who were suspected of collaboration with the enemy. In compositions written during the war, Van Lier expressed his resistance to the deprivation of liberty, especially in his vocal works. After the liberation his work as composer diminished and he focused on his activities as a musicologist, pedagogue and publicist.

by Diet Scholten

Focused, ambitious and a man of principles

Bertus van Lier was born on September 10, 1906, the son of Alfred Johan Salomon van Lier and Cornelia Geertruida Guldensteeden Egeling. Early on, the young Van Lier acquired a thorough musical education. At the age of eight, he took lessons at the music school in his home town, Utrecht. He continued his cello lessons at the Amsterdam Conservatory with Max Orobio de Castro, and attended the Utrecht City Gymnasium. In 1924, he wrote his first composition, Canticum, on the occasion of the 450th anniversary of the school. Known as the ‘Cantus’, this piece remains to this day the school song.

After high school, Van Lier studied privately with Willem Pijper, whose influence was reflected for a long time his compositions. In 1933, he attended a course in orchestral conducting with Hermann Scherchen in Strasbourg. After his studies with Pijper (1926-1932) he worked as a composer, music critic, conservatory teacher and conductor. On the occasion of the completion of the Afsluitdijk in 1937, he composed, upon request of avro-Radio, De Dijk, a rhapsody set to a text by the poet Jan Engelman. In 1938, he became head of the composition department at the Utrecht Conservatory; he also taught at the Rotterdam Conservatory of Music and the Amsterdam Music Lyceum. He wrote articles on music for the newspapers Utrechts Nieuwsblad and NRC Handelsblad. He was a guest conductor of a number of Dutch orchestras. This provided him with the opportunity to draw attention to contemporary Dutch music, including his own works.

Van Lier focused particularly on the linguistic and translatological aspects of his compositions. For Hooglied (Song of Songs, 1949), he immersed himself in the different assumptions on this book of the Bible. He wrote stage music to Sophocles' dramas Aias and Antigone, commissioned by the Utrecht City Gymnasium. Realizing that the existing translations paid insufficient attention to Sophocles' original metre, he made a new award-winning ( Martinus Nijhoff Prize) translation.

Revulsion for Germany

In the third decade of the twentieth century, Van Lier was aware of the great dangers of Nazism. He didn't want to have anything to do with Germany. In May 1936, he refused, as a matter of principle, to send his own work to the Dutch Music Festival in Wiesbaden. He was a member of the Union of Artists in Defense of Cultural Rights (BKVK) and wrote regularly for its bulletin. In the months preceding the Olympic Games in Berlin in August 1936, the BKVK urged artists not to participate in the connected cultural events.

Immediately after the German invasion, he withdrew from public music life. He resigned as music critic for the daily newspaper NRC, canceled his contracts as conductor and on the day of capitulation, dissolved the amateur orchestra he had established in 1939. He was unable and unwilling to contribute to the kind of cultural and musical life the Germans were aiming for. In the words of composer Marius Flothuis:

The German occupation meant for him, as for many others artists, a severe violation of his freedom. As a freelance musician he was not immediately confronted with the difficult choice for, or against the Kultuurkamer (a regulatory cultural agency installed by the German occupying forces) and as a half-Jew he was not in immediate danger. But his path was clear to him from the start and he withdrew completely from public music life, devoting himself to composing, and he became increasingly involved in work for the resistance movement.

In early 1943, Van Lier was sought by the German police and he went into hiding in Amsterdam. Leo Samama writes about this period:

During 1943, he worked together with Rudolf Escher, Paul Sanders and others for De Vrije Katheder. This illegal magazine, established in November 1940 in Amsterdam by students, focused on political and cultural resistance. [...] The opposition against the institution of the Kultuurkamer in 1941, had generated several committees; artists and intellectuals rallied together in rebellion, thus laying the foundation for post-war artists' organizations, and anticipating on future structures of the art world. The best known committees were those from The Hague and Amsterdam; they illegally founded the Federation of Professional Artists in September 1944.

Bertus van Lier was a member of the committee from The Hague.

Music activities in wartime

During the war, Van Lier wrote music essays, organized recitals at home (he loved performing Schubert songs) and composed. He wrote several songs, including Ik sla de trom (I beat the drum, October 1942), a protest song for voice and piano on a text by Jan Greshoff. Subsequently, Van Lier arranged this work for four-part male choir, and either two pianos or orchestra in dedication to his friend Klaas Stempels, who was executed at Fort Rhijnauwen on October 9, 1943. One of the most remarkable works from the war years is the symphonic ballet Katharsis, with a scenario clearly referring to the German occupation.

In 1945, Van Lier composed a few more songs about the war, including Vrijheid (Freedom) for boys choir and organ/harmonium on a poem by Jan Engelman and O Nederlant, let op U Saeck, an arrangment for four-part mixed choir and orchestra based on an ancient song by Valerius.

Investigation of Nazi collaborators

Van Lier was member of the core committee for music of the Federation Artists Associations in charge of investigating Dutch Nazi collaborators. He was one of the authors of the report Saneering van het muziekleven (Restructuring musical life) sent in 1944 to the Dutch government in exile in London. This report mentioned who had stepped the line in making compromises during the occupation, and zoomed in explicitly on those in responsible positions. Being well known was a main factor of this evaluation. This report never reached the Minister of Justice in London and never influenced policy. But when it reappeared shortly after the liberation in Amsterdam, it led to commotion. By order of the military authority, on behalf of the government in London, Honorary Committees had to carry out the investigations. However, there was no legal framework to follow up on these purges. This led to doubts about the assessment criteria and provided room for severe criticism. In return, the authors - or prosecutors - were accused in a brochure entitled Is dat zuivering (Is that purging). Rumors circulated that Van Lier was too harsh in his accusations (particularly to conductor Eduard van Beinum), aiming to become conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, himself. After the war, these exonerative processes moved quickly to the background. On the Van Lier website, his son Hans van Lier describes this development as follows:

In many ways these processes fell into discredit. Some members of the committees withdrew, believing the judgments were too strict or that incorrect criteria were addressed; others, with a keen eye for politics, realized how circumstances quickly changed after the liberation. “Please, let's stop moaning! Then there was the unfortunate hassle about the Mengelbergs. We all had a difficult time! Let the orchestras play, we want music!”

In his own view, Van Lier had encounterd a conflict too large to cope with, a conflict which ultimately led to the division of the building (Concertgebouw) and the Concertgebouw Orchestra. Van Lier was eventually one of the losers. He had to forget his ambitions of becoming conductor.

After the war

On June 9 and 10, 1945, Van Lier and Sanders organized for Maneto (Manifestation Dutch Musicians) the first concert in the liberated Netherlands at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. It was a tribute to musicians who, during the occupation, had not in any way collaborated with institutions of the enemy. Hendrik Andriessen, Guillaume Landre, Johanna Bordewijk-Roepman, Henriette Bosmans and Van Lier were among the featured composers. After the war, Van Lier taught in Rotterdam and Amsterdam. In these cities his memorable concerts of Bach's St. Matthew Passion - with the famous tenor Peter Pears as evangelist - attracted large audiences. He demonstrated his own very particular vision of the performance. Choir and orchestra I were engaged in the biblical text. In the Lutheran Church, a round space, choir and orchestra II were situated under the pulpit, and Pears sang from the pulpit. Another choir, representing the worshippers, commented on the bloodcurdling biblical events. Van Lier was also one of the first in the Netherlands who performed Bach's St. Matthew Passion with a small group, consisting mainly of amateurs.

For 15 years as music critic for the daily newspaper Het Parool, he wrote previews, reviews and essays. Composing was diminishing. But he continued to conduct; also as regular guest conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra and the Residentie Orchestra. Benjamin Britten invited him in 1950 to direct the St. Matthew Passion at the Aldeburgh Festival and in 1956, he directed the Dutch Chamber Orchestra at the Holland Festival. Van Lier remained active as a musicologist, educationalist and publicist. Already in 1948, Buiten de maatstreep, a selection of his music reviews, was published.

Van Lier's theoretical and historical interest in music obtained academic recognition. As of 1960, he taught musicology at the University of Groningen. Between 1961 and 1971 he conducted the student orchestra Bragi and made it flourish. He was appointed as university lecturer in 1966. Rhythm and Metrum - title of his public lecture - were recurring themes in his thoughts and works. In 1972, he died at his home in Roden.

Van Lier's music

In the Biographical Dictionary of the Netherlands, Marius Flothuis writes:

Initally, Van Lier' s style was greatly influenced by Pijper. This is very clear in his Symphony no. 1 (1928), Sonatina No. 2 for piano (1930) and Four songs on lyrics by Leopold (1933). Polytonality is evident in later works [...], but apparently Van Lier needed a tonal center, as can be heard in his Symphony no. 3 (1939) and the song Liberty (1945) composed during the German occupation. This applies particularly to the cantata O Nederland, let op Uw saeck (1945), based on songs from Valerius' Gedenck-Clanck. Some works possess a melodic and rhythmic complexity leading to an imbalance in the instrumentation. The Concerto (1950) for bassoon and orchestra and Symphonia (1954) suffer from a certain degree of overabundance in the instrumentation. His most notable works include the ballet Katharsis (1945), which he wrote during the German occupation. [...] Bertus van Lier is one of the most versatile Dutch musicians of his time. His composition students included Nico Schuyt and Robert Heppener.

Sources

www.bertusvanlier.nl

Biografisch Woordenboek van Nederland

Dungen, Geert van den, Bertus van Lier (1906-1972), doelgerichte gedrevenheid in dienst van principes (www.wo2-muziek.org)

Micheels, Pauline, Muziek in de schaduw van het Derde Rijk. De Nederlandse symfonie-orkesten 1933-1945 (Zutphen, 1993)

Samama, Leo, Nederlandse muziek in de 20-ste eeuw (Amsterdam, 2006)